When I first landed in venture, it was with an early stage focus: predominantly Series A. The body of knowledge available to founders raising a Series A was pretty robust at the time thanks to investors demystifying a once opaque process via public blogs and forums. YC has since added even more transparency, creating a great Series A guide for founders looking to raise a Series A.

As I’ve move into a multi-stage environment (early + growth), I’ve been surprised by the dearth of information on fundraising for growth rounds, particularly that first growth round: the Series B. There are of course lots of good posts focused on metrics of all sorts, scaling in the growth stages, etc, but the existing literature doesn’t really cover how to raise a Series B — and certainly not in a tactical way.

This is particularly relevant in a post-covid world. If you look at the Pitchbook data from the last few quarters across stages, the story is quite interesting. Early stage deals (Series A) and late stage deals (Series D), saw a massive drop-off in dollars invested between Q4 ’19 and Q1 ’20 but then a decent sized recovery in Q2 ’20 (not all the way back but venture dollars returned 30%+ and the upward trend will likely continue into Q3 ’20.) Series Cs actually saw an acceleration through Covid.

The Series B round, however, while declining in a more measured way, continued a several quarter decline with almost no recovery from Q1 ’20 to Q2 ’20.

My hypothesis here is that the market is bifurcating around this new “ugly duckling” round — creating something like the Series A crunch of 2015. Why is that? At the Series A, investors can put in a relatively small check and get higher ownership to compensate for the risk taken. Not every Series A needs to work; high ownership in a few measured bets can return a fund making up for losses elsewhere.

In the later stage rounds (e.g. C and D), the winners start to become much clear and there is plenty of later stage capital ready to go to work into obvious winners. The returns in the later stages may not be as out-sized as at the A, from a multiple perspective, but a big check can return a sizable dollar amount at a decent IRR while ensuring investors are unlikely to take a 0 on any given investment.

But that first growth round (Series B) is becoming an increasingly difficult round for investors (and, consequently, for founders.) The company is perhaps somewhat de-risked from a PMF perspective but there are still substantial GTM and scaling questions that need to be answered. As such, Series B investors are forced to put fairly sizable checks to work ($20–$40M) without the ownership level of a Series A or the “certainty” of a later stage round. This becomes a bit more amplified in a post-covid world where there are even more unknowns.

This post is my attempt to shed some light on how to approach the Series B so that you can raise a successful first growth round.

A Quick Preface

Before we get started, because the letter of the alphabet can mean many different things to different people, I’ll begin by caveating what I mean when I say “Series B.” The profile for most companies going out to raise their first growth round (i.e. Series B) looks something like:

- ~$5–$10M ARR (though the range has become much wider on both ends)

- To-date has raised anywhere from $5M to $25M (across angel, pre-seed/seed and A rounds)

- Raising ~$20–$40M with a single lead or co-lead(s) doing the majority of the round

- Has anywhere from ~2–4 years of financial history; company likely ~4–6 years old

- Original founder(s) most likely still at the helm and running the day-to-day

This is, of course, overly simplistic as Series B companies have a broader range of profiles (so bear with me!) I will also assume a SaaS business model (though the learnings could be extrapolated to other B2B models, including hybrid models, which I have previously written about here.) I’ll also briefly mention that many of the lessons discussed below for the Series B also extend into later-stage rounds (e.g. Series C, D, etc.)

Building on the A

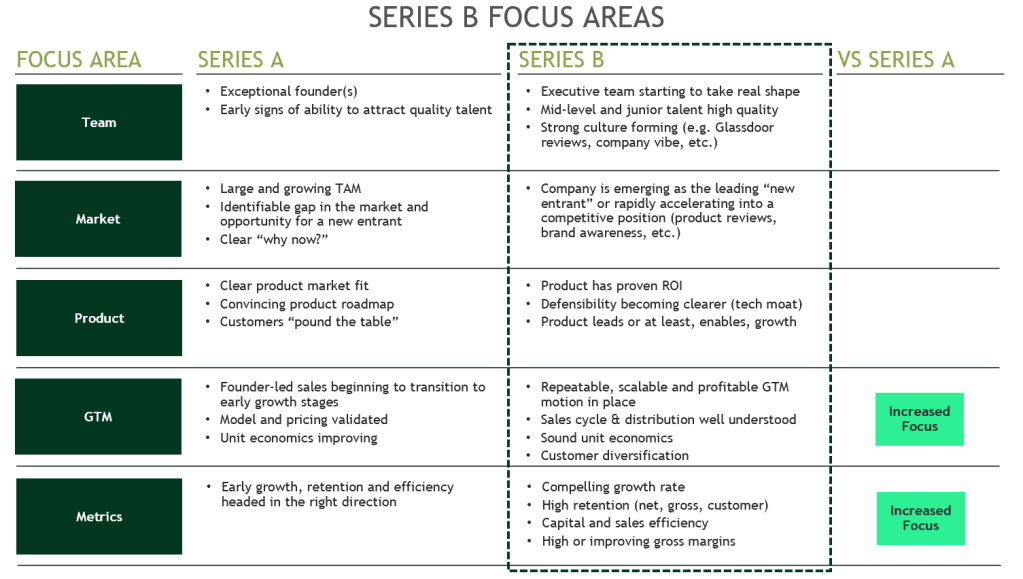

The best way to frame the Series B and how investors will evaluate your company is through the lens of “building on the A.” Most investors, generally speaking, focus on five key areas: (1) team, (2) market, (3) product, (4) GTM and (5) metrics. The first 3 have some additional features that build on what was established at the Series A while the latter two have a materially increased focus vs the Series A.

This is probably obvious: more time in the market means more data investors can analyze to assess whether a company has the potential to scale into an enduring brand. Let’s take a closer look at each of the 5 focus areas and how the Series B builds on the A.

Team

At the Series A, investors are looking for exceptional founders (passion, vision, grit, deep knowledge, charisma, etc.) There is a lot to unpack there but that is a separate post on its own! We are also often looking for early signs that the founders can attract high quality talent in the form of early team hires.

At the Series B, much more attention is paid to the broader executive team and how it is starting to shape up. In addition to assessing your ability to recruit great functional leaders, who have their own strong follower-ship, investors tend to start thinking in terms of “gaps that need to be filled” as part of the post-B phase of growth. Maybe you are at the point where you need a VP of Sales to lead GTM. Maybe the founder needs to transition product to a VP of Product to focus on other areas. Or maybe it is everyone’s favorite: time to hire that seasoned COO to support the young first-time founder!

The other area Series B investors will start to focus on is culture. Often by the B a distinct “cultural ethos” has started to form. Investors will try to glean what sort of vibe your startup has and how it is perceived in the market. This can be accomplished by spending time on-site at the office, looking closely at employee NPS and digging around to see what can be found “outside-in” via channels like Glassdoor. In a post-covid world, where in-person visits are now much harder, a company’s digital footprint will likely matter even more. Investors will also spend more time 1:1 with key executive leaders over video.

Market

When raising the Series A, the market story needs to be one of a large ($10B+) and growing (5%+ CAGR) TAM. There also needs to be some story around a gap in the market or a greenfield opportunity enabled by sleepy incumbents underserving some portion of the market (e.g. SMBs, developers, a new function like SalesOps, etc.) Articulating a clear “why now?” is also a very important part of the fundraise story.

At the Series B, investors will look for validation of the story you told at the Series A and whether the early momentum backs up that story. It is most compelling if your company is very clearly emerging as the market-leading new entrant. Investors will validate that by speaking with customers, reading product reviews from G2 and digging around on sources like Pitchbook and Google trends, to understand brand awareness and signal.

Product

Demonstrating early signs of product market fit at the Series A is paramount. In the end, this may be the single most important factor (outside of the founders) in determining a successful A raise. Investors will look for customers who “pound the table” and sticky enterprise user behavior. Beyond that, they will look at the road map to see if it is compelling and headed in a direction that matches the broader vision.

At the Series B, there are a few more product-components that matter. At this point, the product should show a clear and quantifiable ROI for the customer. There should be case studies and “customer-wide data” that demonstrate the ROI (whether it is cost savings, revenue lift or some other metric.) It also often helps if the product is developing in a way where there is a tech asset that creates a broader moat.

GTM

Relatively less attention is paid to GTM at the A. At that stage, founder-led-sales is common — though there may be some early signs of a transition to non-founder AEs. Typically the pricing and delivery model has been validated at the Series A. End-state unit economics (e.g. LTV:CAC, payback, etc.) are largely theoretical but improving quarter over quarter.

When you set out to raise the B, investors will be looking for a tighter story around GTM. They will look to see a scalable, repeatable and profitable motion in place. At this point you should have a pretty well understood sales cycle (e.g. how the funnel gets filled, how much time is spent at each point, what % convert, etc.) The unit economics that were theoretical at the A should be more proven-out at the B.

It is also really powerful if you have diversified the customer base. If moving “bottoms up,” for example, you may have a core startup-base of early adopters but now also have a strong set of mid-market logos, maybe even some 6-figure enterprise ACVs. You may have also started diversifying from one industry to several — this has become particularly important post-Covid when it has become clear that reliance on 1 vertical, even if performing well, can lead to a very false sense of security.

Metrics

Perhaps the biggest difference between the A and the B is that the availability of data makes the numbers matter a lot more. Much has been written about metrics but the most important areas to focus on at the B are:

- Growth rate: demonstrating the company is on a “triple-triple-double-double-double” trajectory is commonly acknowledged as the ideal path. While that is the gold standard, the reality is most companies are not going to be on that trajectory by the time they raise a B. And different companies hit their stride at different times. A more simple goal around the B, is that you should try to be growing at least 100% yoy to attract high quality investors.

- Retention: High net dollar retention is what you will ultimately be judged on because that is, in the end, what matters most. But pay attention to gross dollar and logo retention as well. Some great barometers to benchmark against, depending on the underlying GTM motion and customer base are here and here.

- Efficiency: Both capital efficiency and sales efficiency (sub-category) are key operating levers to scale your business successfully beyond the Series B. Aim to have an efficiency score as close to 1 as possible and your magic number should likewise be around 1 as well. As I’ve written before, efficiency is even more important in today’s post-covid world.

- Gross Margins: Most SaaS businesses are naturally blessed with high gross margins (80%+) — though those margins may take time to materialize. You may also have a hybrid model with multiple revenue streams. Showing high or improving gross margins at the Series B is important as it helps investors buy into the dream that your company can command high multiples at exit.

Running the Series B Process

Now that we have covered the fundamentals of what you will be evaluated against at the B, let’s turn our attention to how to run an effective process. Don’t under-estimate the importance of running a tight and well-managed process. A successful raise is more likely to happen with careful planning.

Note: If you are 1–6 months out from raising a Series B, skip this first section and move to the next section: “Build the Right List of Investors.”

Backwards Plan

The first thing to realize is that as soon as the Series A closes, the “clock starts ticking” for the B round, which typically happens 18–24 months after the Series A — though timelines may stretch a bit longer in this current environment. When the Series A closes, start thinking about where you want to be when you raise the B. Some questions to ask:

- What is the top-line ARR goal for a compelling B?

- How much capital will be consumed between now and then?

- What does net retention need to look like (and broader cohort trends?)

- What is the target gross margin?

- What are the key exec-level hires that need to be made?

- What product milestones need to be hit?

Once you have the Series B goals written down and aligned with your team and Board, figure out the quarter-by-quarter plan to get there. Be thoughtful about what you aim to accomplish each quarter and hold yourself accountable to the quarterly milestones. The plan will change, but you are much more likely to have a successful Series B raise if you are deliberate about planning the journey to get there.

Build the “Right” List of Investors

Another important thing to do shortly after the Series A is to build a list of the right set of investors. Many founders end up wasting time talking to investors that are just not going to be the right fit for reasons that are “strategy-related” (e.g. stage or category.) For example, many Series A focused firms do not invest in Series Bs — check size is too high, ownership too low or valuation not in range for their strategy. Other, later stage firms, don’t do Series Bs — it’s just “too early.” If a firm is not investing out of a fund of at least $250M, they are unlikely to lead a Series B round of $20M+.

Some firms have areas they won’t touch (i.e. “we don’t do consumer.”) Others will only follow once a lead is identified. Corporate VCs/ strategics can add a lot of value, but may also take much more time. As a founder, you may also be inundated with inbound from various firms who are simply prospecting or doing research on a space. Bear in mind most firms invest in <1% of the companies they talk to. So taking meetings with lots of firms can be time consuming and distracting from the core business.

My suggestion is to “go deep, rather than broad.” Work with your existing Seed and Series A investors to craft a highly targeted list of ~10–15 firms worth getting to know more intimately. If you don’t have an existing relationship with those firms, have one of your investors provide you with a warm intro.

Allocate some amount of your time (but definitely <5%) to building deeper relationships with these firms over the course of 1–2 years — and specifically with the person at that firm who would be sponsoring the investment. This will allow you the opportunity to really assess whether they would be a good long-term partner. It also allows the investor to get to know you and to socialize the opportunity internally so that you are a “known entity” when it comes time to formally raise.

Create the Data Room

In the weeks before you decide to kick-off the formal raise process, you will want to have your data room fully structured and ready to go. Do not start the process before you have this in place! Frequently founders underestimate the pain caused when they prematurely kick-off a process and have 10–15 firms asking for different data items.

Create a single, well-structured data room with everything a firm could possibly want to know and have that ready to go. You will come off as more structured/together and will also limit the back and forth requests and internal scramble that comes with being less prepared. See below for an example of how to structure your data room and the items to put in each folder.

Another best practice is to have a “go-to” list of 5–10 customers who can serve as reference checks for investors. Have these customers prepped in advance of your fundraise. Try your best to spread the customer references around as no customer wants to spend their whole day talking to VCs — no matter how much they love your product!

Rehearse the Pitch

In the few weeks before you go out to formally raise, focus on practicing the pitch. This includes understanding timing (you will typically have 30–60 minutes) depending on where you are in the process with any given firm. You’ll have to understand pacing and how to deliver concise responses. We are also in a hybrid environment right now, so be prepared for a mixture of phone, video and (perhaps) some in-person.

Another important dimension is who to bring to the meeting. In the early parts of the process the founder/CEO should be doing the meetings 1:1 but as you progress, you’ll likely need to bring in co-founders and other key exec team members. Have a plan of who you are going to bring in and at what point in the process. The firms you are speaking with may make suggestions as you progress through their process. To minimize disruption to the team, ask for the level of “seriousness” before taking team member’s time away from the business.

I also highly recommend that before you go out to formally raise, practice the pitch with your earlier investors. When you do this, ask for a sub-group of the broader firm to round-out the perspective of your lead sponsor with fresh eyes. A good way to think of this is a 60-minute pitch session where you pitch the team on doing their pro-rata. Have your lead sponsor collect the feedback from the team and share it with you. Incorporate the feedback before you go out.

Manage the Process

Once you formally go out to raise, realize that this is your full-time job and will require 100% of your time/ energy to succeed. You will also likely need to designate someone on your team as a “diligence-point-person” (e.g. VP of Finance, COO, etc) to field requests from potential investors. So make sure to have a process in place internally.

In addition, be sure to create a timeline of when first meets happen, when you want to receive term sheets by and the steps in between. Try to keep all the firms you are working with on a similar schedule. If a few jump the gun, that could create a forcing function for others to catchup and accelerate their process, but it could also result in some firms getting turned-off by a fast process. Never create a false sense of urgency or exaggerate where you are in the process.

While there is a loosely similar process across firms, each firm runs their “deal pipeline” slightly differently. When it comes to getting a decision, there is an even broader spectrum (in some firms it’s totally up to the sponsor, in other firms there is a vote and at some places there is just 1 decision maker.) As you move further into the process with any given firm, ask the lead sponsor (your original point of contact) for clarity on process and how decisions get made. This will help you a) understand the steps to a TS and b) allow you to best position yourself to navigate internal dynamics.

In general, black swan events notwithstanding, good Series Bs happen in ~4–8 weeks from intro session to TS in-hand. Sometimes things can move much quicker — especially if you have an existing relationship with a firm. If the round is taking longer than that, there is likely low interest and you may need to re-think the strategy. Explained “Nos” (if you actually get an honest explanation) can be helpful in terms of adjusting the strategy. At the same time, don’t read too far into a pass because there are a thousand reasons for passing that are well beyond your control. For example, a firm has decided they have already made 1 bet in your space and don’t want to do another.

There are differing opinions on valuation, but in my experience, it is never a good idea to throw out a number when pitching VCs. If the number you suggest is too high, you can quickly turn-off an investor who might otherwise be interested. If an investor asks you what valuation you are looking for say something to the effect of: “We care more about finding the right long-term partner than optimizing around a specific number. We have made considerable progress since the Series A and hope for the Series B valuation to reflect the value accrued, but we will let the market set the price.”

Close the Deal

Once you have succeeded in getting a few term sheets, it’s time to evaluate and make the right decision. Remember you are going to be working with the firm you choose for the next 5–10 years, so choose wisely. The first thing to do is a hygiene check on all the terms. Have your legal counsel and Series A investor take a look and make sure there aren’t any problematic terms.

Many founders get caught up in maximizing valuation but be careful here — the highest price isn’t necessarily going to be the right fit long term. It’s totally fine to use the leverage of optionality but pick your battles wisely and make sure to prioritize accordingly.

You should also run your own diligence on the firm you are working with. Ask for the firms you are evaluating to provide founder references but also do your own back-channel diligence. Get on the phone and spend time understanding how the firm has historically behaved. How involved are they? Do they contribute meaningfully? Do they operate with a steady hand through the highs and lows of company building? Do other founders like working with them? Ask for examples — the more specific the better.

Concluding Thoughts

Raising money is almost never a fun thing for founders. But the right founder/VC pairing can be a powerful acceleration to help you achieve your vision. Understanding what Series B investors look for and how to manage your fundraise is the key to success. Hopefully with a lot of careful planning and a little bit of luck, you will end up with a successful Series B outcome.

As a final parting thought, I’ve aggregated the thoughts above into a packaged view (“Series B checklist”) of the things to do before you raise your first growth round. Remember, you don’t necessarily need to have all of these checked off. But the more you do, the more compelling the round will be.

As always, please reach out with any thoughts or suggestions (@MrAllenMiller). I’d also like to thank Kris Rudeegraap (@rudeegraap), Michelle Palleschi, Rishi Taparia (@taps), Ricky Pelletier (@RickyPelletier), Parsa Saljoughian (@parsa_s), Preeti Rathi (@preet1rathi) and Lenny Rachitsky (@lennysan) for their help in reviewing early drafts of this and providing invaluable feedback.