Over the course of the last century government has always found a way to influence the course of business through regulation. Traditionally, however, the government has tended to focus regulatory efforts on large enterprises. The vast majority of startups often fly under the radar as they are too small to really create concerns for regulators. The select few that do balloon into bigger companies through super-sonic growth, i.e. the Ubers and AirBnBs of the world, often do encounter regulatory hurdles as they grow into large enterprises. The reality, however, is that government regulation, in certain industries, can be game changing even at the earliest of stages. We need look no further than peer-to-peer (P2P) lending as an example.

Going back a decade to the mid-2000s, P2P lending was a nascent industry that had begun to shape into a two-horse race between Prosper (founded in 2005) and Lending Club (founded a year later in 2006). At the time, U.S. consumers had about $880 billion in credit outstanding and the virtual marketplaces for P2P lending were thought to reach $300 billion in loan origination per year by 2025. It was (and still is) a huge and growing market with lots of potential. As the first mover in the space, Prosper had jumped out in front by the end of 2007, facilitating 10x the number of loan originations as Lending Club. But 7 years later, Lending Club went on to IPO in December of 2014 and now has an enterprise value of $9.6B. Prosper has fallen to a distant 2nd and has struggled to find demand for an IPO—withdrawing its filing process on numerous occasions. So what happened?

The answer is government regulation, which provided Lending Club with a huge competitive advantage over Prosper in the early days of P2P lending. The critical issue that came up in 2008-2009 was over whether the SEC would view the loan transactions Prosper and Lending Club were facilitating as promissory notes, without any filing requirements, or securities, which (at the time) had extensive and very expensive filing requirements.

Prosper took a more passive “wait and see” approach to this regulatory issue—hoping that regulators would simply view the underlying assets as promissory notes and leave them alone. Lending Club, however, had the foresight early on to see the danger with this approach. If the industry was forced to file with the SEC, everyone would have to shut down for 6 months and submit to the long and expensive registration process. As such, Lending Club chose to take a proactive approach in being the first movers to file. Moreover, they actually helped the SEC shape much of the regulation in P2P lending which provided them with a huge short-term advantage over the competition.

As soon as Lending Club finished their filing process, the SEC then ruled that every other P2P lending marketplace would have to do the same. This meant that they came out of the process right when everyone else had to temporarily shut down for 6-9 months. So for ~9 months (time it took Prosper to emerge from the process) they were effectively the only player in P2P lending, right as the market took off courtesy of the tailwinds provided by the financial crisis.

Many of the other early players essentially shut down due to the heavy costs of filing and the lost time. Prosper managed to hobble out of the process but by then the damage had been done. With 9 months of green field, Lending Club had built out both sides of the two-sided marketplace, enhanced their network effects and customer captivity and emerged as the #1 player in P2P lending. The last 5 years Prosper has been playing catch-up as best it can. So government regulation was game-changing early on in P2P lending.

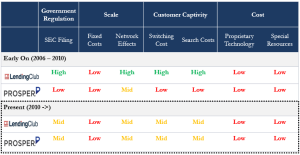

However, the story doesn’t really end there. While Prosper and Lending Club continue to do pretty well, the challenge for both of them is that they don’t have much by way of long term competitive advantages. The image below shows their respective competitive advantages at 2 different points in time.

We’ve already discussed the early days of P2P lending, so let’s shift our focus on what is happening now in 4 cores areas: (1) government regulation, (2) scale, (3) customer captivity and (4) cost.

- Government Regulation: Having cleared the SEC regulatory filing process, Prosper emerged wounded but alive. The problem with regulation now, however, is that in many ways Propser and Lending Club cleared the way for everyone else. The SEC filing process is now much faster and less costly. So there no longer exists a true competitive advantage for either from a regulatory perspective.

- Economies of Scale: Neither Prosper nor Lending Club ever had an advantage in terms of fixed costs. These are software marketplace business that are not capital intensive; that basic principle remains true today. What has changed is the strength of the network effects.

- Since dropping the auction-style borrower/lender matching process and migrating to the Lending Club method of assessing credit risk (through FICO scores and other metrics), the number of credit-worthy borrowers and therefore lenders willing to lend has increased tremendously on Prosper’s platform. The result has been a strengthening of Prosper’s network effects. They have now done $2B in total loan origination, which is a third of the $6B Lending Club had done.

- The challenge though for both Lending Club and Prosper, however, is that the networks effects are not unique to their platforms. Lenders are simply in search of credit-worthy individuals in this low interest rate environment. As lenders on these platforms continue to move away from individuals and towards institutions, they will be increasingly more willing to multi-home across multiple platforms in search of the most credit-worthy borrowers and the highest yields. Borrowers will also multi-home in an effort to find the lowest interest rates as well as the most personalized / specific marketplace—hence the rise of P2P lending in specific verticals (more on this below).

- Customer Captivity: Admittedly, I don’t have much by way of evidence but my belief is that as network effects begin to dwindle on both Prosper and Lending Club, so too will customer captivity. This will be most notable in terms of customer acquisition costs. Around 2010/2011 it cost Lending Club ~$40-$60 to acquire each borrower and ~$20 to acquire each lender. I am positive that this is higher than CAC in 2009-2010 when Lending Club barreled its way out of the SEC filing process as the only player and lower than what they will have to spend in years to come to acquire customers. Expect to see marketing and sales spends as a % of revenue to increase as well as higher churn and a lowered ARPU/CAC ratio.

- (Supply) Cost: Early on, Lending Club and Prosper may have had a slight supply advantage in terms of proprietary knowledge and/or special resources. Their algorithms matching borrowers and lenders as well as probability of default may have provided them with a slight edge—particularly given the larger amounts of data they had as a result of being in business longer than others. Unfortunately, this too is not a sustainable competitive advantage. The technology in P2P lending over time has become increasingly commoditized—there are only so many ways you can assess credit-worthiness and, given enough brain-power and time, the technology can be easily replicated.

So the overall affect for both Prosper and Lending Club has been a weakening of their competitive advantages vis a vis the rest of the P2P lending market. This has resulted in a whole slew of new entrants fighting for share and cutting into the once high (as high as 40% for Lending Club) margins. Here’s a look at how the competitive landscape is shaping up today:

In particular, the last few years have given rise to vertically focused P2P lending marketplaces. These vertical P2P lending marketplaces focus on specific verticals like student lending (SoFi, CommonBond, etc.) or SMB lending (OnDeck, CAN Capital, etc.) Because they offer a specific focus or thematic lending opportunity, the network effects and customer captivity of these offerings tends to be high. While still mostly small and narrowly-focused, these vertical P2P lenders have broadened the P2P lending marketplace into more than just a 2-horse race.